Finding Your Roots

Great Migrations

Season 12 Episode 2 | 52m 9sVideo has Closed Captions

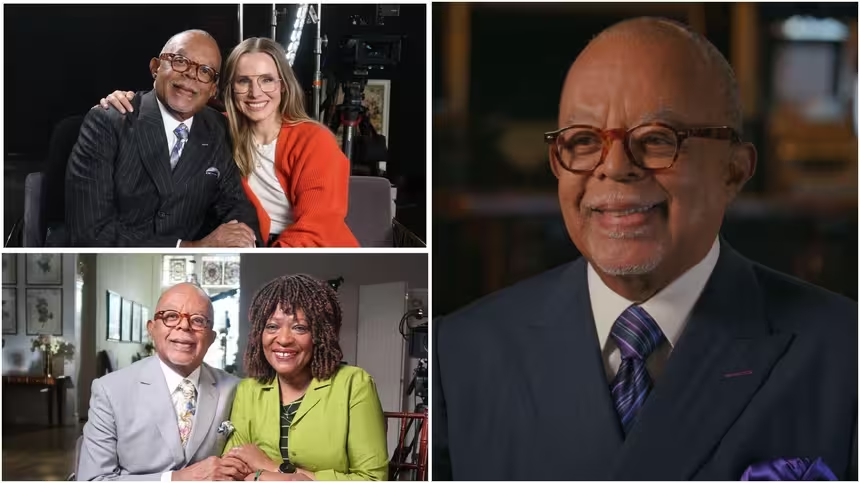

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. maps the family trees of rapper Wiz Khalifa and actor Sanaa Lathan.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. introduces rapper Wiz Khalifa and actor Sanaa Lathan to ancestors who left the American South in search of new jobs and better lives in the North, boldly breaking racial barriers . Journeying into the depths of the Jim Crow era, Wiz and Sanaa reimagine themselves as they learn the heroic stories of the people forever transformed their families.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Great Migrations

Season 12 Episode 2 | 52m 9sVideo has Closed Captions

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. introduces rapper Wiz Khalifa and actor Sanaa Lathan to ancestors who left the American South in search of new jobs and better lives in the North, boldly breaking racial barriers . Journeying into the depths of the Jim Crow era, Wiz and Sanaa reimagine themselves as they learn the heroic stories of the people forever transformed their families.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGATES: I'm Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Welcome to Finding Your Roots.

In this episode, we'll explore the family trees of actor Sanaa Lathan and rapper Wiz Khalifa, meeting ancestors who made incredible journeys.

KHALIFA: You think that your history is that deep, but to actually see, you know, black male, 14, and then see him turn into a human being, a person.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: That's amazing.

LATHAN: It's just emotionally overwhelming and, you know, I, I, I, I wanna know more.

GATES: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available.

Genealogists comb through paper trails, stretching back hundreds of years.

LATHAN: This is amazing.

GATES: While DNA experts utilize the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets that have lain hidden for generations.

KHALIFA: This is mind-blowing.

GATES: And we've compiled everything... LATHAN: Oh my God.

GATES: ...into a Book of Life.

KHALIFA: Damn.

GATES: A record of all of our discoveries and a window into the hidden past.

LATHAN: I didn't know this was gonna be such a spiritual journey you're taking me on.

GATES: That is your family in the first federal census to list all African Americans.

KHALIFA: Wow.

That's insane.

That's awesome.

LATHAN: It's just fascinating to think of all these different people that have kind of contributed to the soup that I am.

GATES: Sanaa and Wiz both descend from people who made immense efforts to change their fortunes, traveling great distances with little more than a dream.

In this episode, they're going to meet the ancestors who made those journeys and uncover the stories that got lost along the way.

(theme music playing).

♪ ♪ (book closes).

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ GATES: Wiz Khalifa is constantly smiling, and with good reason.

He's one of the best-selling Hip Hop artists of all time, and he's risen to the top, thanks to his utterly genuine exuberance.

But for all the joy he brings to the stage, in the studio, Wiz is a meticulous craftsman with a tireless work ethic, traits that have marked him since he was a child.

KHALIFA: My mom really figured it out.

She started seeing me, taking it serious 'cause I would be like writing rhymes and I had like, rap books laying around the house, and I kind of explained it to her, like what our lingo was and what it all meant to me.

So, she was like, "All right, cool, whatever."

Not whatever, but like, "Yeah, cool."

Like, you know, "I support that."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: And then the following summer, I went and lived with my dad, and I told him the same thing about how serious I was about making music.

And he, you know, he, he allowed me to dive all the way in.

He was like, if that's something that you want, do, I wanna see you take it serious, like, don't just say you're about it, you know, really do it.

GATES: So that's when you decided, "That's what I want to do with the rest of my life."

KHALIFA: I loved basketball at the time.

There was like a short period of time when I lived with my dad, like that summer that I was telling you about... GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: Where I did normal kid stuff, like, you know, played sports, uh, went to games, did all of this stuff.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: But I put the ball away.

I wanted to do music.

GATES: Wiz's ambitions would quickly bear fruit.

In 2005, while still in high school, he signed a deal with a small label and released his first mixtape, restyling his hometown of Pittsburgh as "Pistolvania" and declaring himself "a prince of the city."

It was an instant success, but it wasn't exactly the way Wiz wanted to be seen.

So, he made a change.

KHALIFA: I was trying to be hard.

Um, everybody was like, tough at this time, and like, I wasn't really a tough guy.

I, I, I hung around some tough people.

Well, I'm not gonna say I wasn't a tough guy, 'cause you gotta be tough to come up in Pittsburgh.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: But I wasn't like, you know, that wasn't really my thing of how, like, you know, what I would do to you.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: And, um, my music was, you know, based on like how good I was, like at picking out beats or writing hooks or, you know, making verses come together.

GATES: Right.

KHALIFA: And I was able to find a lane where, like, it wasn't back then where it is, like you had to be tough.

It's like you could be, you know, funny.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: You know, you could be, uh, a little, a little goofy, a little bit, you know what I'm saying?

But you could still be smart and educated.

GATES: And no one else had done it.

KHALIFA: Yeah, nobody else had done it.

So, when I started seeing that paying off, and I was like, I'm just being myself, and I'm able to create, um, at the pace that I want to, I knew that that was gonna take me to the top.

GATES: Once he began to embrace his own voice, Wiz couldn't be stopped.

He's gone on to release eight albums and over 80 singles, including "Black and Yellow," a massive hit that reached number one on the Billboard Top 100.

Yet through it all, Wiz has never lost his passion or his drive.

KHALIFA: I think what I did was just outwork a lot of people.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: On top of making music, I'm shooting videos, I'm editing videos, I'm staying, uh, engaging with my fans.

I'm doing the artist job and the label job at the same time.

GATES: Wow.

KHALIFA: Yeah, and I was promoting myself; I was marketing myself, and I was doing all of the things that, you know, people wish that somebody could do for them.

I was doing them for myself.

So, I, that's definitely what put me ahead, is that attitude and just knowing that, um, you know, I enjoy doing that stuff; nobody had to make me do it.

It wasn't nobody dangling a check in front of me or anything.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: It's not like an end goal or an end result or anything, it's just this forever fire that kind of burns.

GATES: My second guest is actor Sanaa Lathan, fame for her star turns in Love and Basketball, The Best Man, and Succession.

Much like Wiz, Sanaa found her calling at a young age, but under very different circumstances.

Her mother was an actor and dancer, her father, a director and producer.

And Sanaa never wanted to do anything but follow in their footsteps.

LATHAN: I grew up in the theater, Mommy was, she was in the original Alvin Ailey company, and when I was a toddler, she was in the original "Wiz" on Broadway.

GATES: Wow.

LATHAN: With, uh, Stephanie Mills and Eartha Kitt.

And Eartha Kit kind of took her under her wing, and she got to kind of share a dressing room with her.

So, I was always there toddling around, behind the scenes, and so, you know, some of my earliest memories were me, like in the, in the mirror as like a 4-year-old pretending to be Eartha Kitt, you know?

And I would walk out on the stage after the, the, the, um, theater was empty with the, the, that single light... GATES: Uh-huh.

LATHAN: ...and stand out there and look out there.

So, I think early on I felt like, yeah, this is what I'm gonna do.

GATES: Sanaa would soon discover that she had determination as well as dreams and that she was going to need it.

She began acting as a teenager and showed talent right away.

But when she was accepted by the prestigious School of Drama at Yale, her father was not exactly thrilled.

LATHAN: He literally almost cried; he was like, "You can't be an actress."

GATES: Really?

LATHAN: Yes.

GATES: Oh my God.

LATHAN: Because he just didn't want me to go through the pain of what it is to be an actor.

GATES: Uh-huh.

LATHAN: And, you know, one per my acting teacher at Yale, literally the first day of acting class, said, 1% of people who pursue this make it.

GATES: Right.

LATHAN: So, you gotta be pretty, you know, non-realistic... GATES: Yeah.

LATHAN: ...in order to pursue it, and Dad had been living it.

He was like, it doesn't matter how talented you are.

GATES: Right.

LATHAN: There's no roles.

GATES: This is 1% of White people.

LATHAN: 1% of White people make a living at it.

So, he's like, there's no roles.

He's like, you know, you're so, you're so smart, you have so much... He's like, he just didn't want me to suffer.

GATES: Mm-hmm, of course.

LATHAN: But I was like, "No."

GATES: Happily, Sanaa listened to herself and beat the odds.

Just three years out of Yale, she got her first big break in the cult classic Blade, and she's never looked back.

Sanaa has been working constantly, ever since; in the process, she's not only calmed her parents, she's kept them close.

LATHAN: You know, my mother to this day, she's my scene partner when I am learning my lines, like I will zoom with her, I'll be in London, I'll be like, "Mommy, we gotta go over my scene for tomorrow."

So, she's like in the trenches with me.

She can even give me notes, you know, "I'm not believing you," "You like need to drop it in."

(laughter).

And Dad has just always been that support.

Like, I remember when I first came out to LA, and I would be screen testing for things and, you know, it'd be between for a great job that I thought was like "it" and I wouldn't get it.

And I, you know, back then, you'd be really destroyed.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LATHAN: And that's the gift of having somebody, 'cause I saw in his eyes, and I trusted what he was saying, like, "You will be fine.

Keep going, keep working hard, keep doing your best."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LATHAN: "Every audition, it's money in the bank, and it'll come around."

GATES: And you took that to heart.

LATHAN: Exactly.

GATES: My two guests have very different backgrounds, but share a common thread.

Each of their families was transformed by ancestors who took extraordinary chances.

Yet somehow the stories of those ancestors have not been passed down.

It was time for that to change.

I started with Wiz Khalifa and with his maternal great-grandfather, a man named Willie Wimbush, Jr., or "Papa Bush," as he was affectionately called.

Wiz, was just a teenager when Willie died, and he knew almost nothing about his life.

KHALIFA: He was pretty chill from what I remember, but I was the baby.

GATES: Oh, right.

KHALIFA: So, anybody who got to experience Papa Bush, I know he passed away in '06, but, um, you know, we moved around a lot, so I didn't really get to see too much of Papa Bush.

GATES: Ready to see what we found?

KHALIFA: Let's go.

GATES: This is a record from the National Archives.

Would you please read the transcribed section in the white box?

KHALIFA: Registration card, Willie Wimbush, age 18, date of birth, May 3rd, 1924.

Place of birth: Barnesville, Georgia.

Race, Negro.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: Date of registration, June 29th, 1942.

GATES: That's his draft card.

KHALIFA: Papa Bush was in World War II?

GATES: Yes.

KHALIFA: Damn.

GATES: 1942, World War II is raging.

KHALIFA: Damn, Papa Bush!

GATES: Willie registered when he was just 18 years old and was assigned to the Quartermaster Corps, then sent to training camps in Virginia and Texas.

At the time, the United States military, like most of America, was segregated, so Willie served in an all-Black unit, likely under a White officer.

What do you think that was like?

KHALIFA: Yeah, at that, at that time?

GATES: Yeah.

KHALIFA: Back then?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: Yeah, he probably got called a few "Ns," not "Negro."

(laughter).

GATES: You got it.

Please turn the page.

These are two letters from Black men who went through military training with the Quartermaster Corps around the very same time as your great-grandfather.

Would you please read the transcribed sections in the white box?

KHALIFA: "The company as a whole has a part to play in this war, which is for the survival of our ideals and the opportunity to carry on the fight for democracy that serves one and all equally.

We're ready, willing, and able, but we're not going to accept the conditions our battalion commanders are trying to force upon us.

He is a rough dried, leatherneck Negro hating cracker from Louisiana, who has insulted all Negroes in general.

Calls our women everything, but women.

Misuse soldiers..." GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: "...treats us as if we were in a forced labor camp or chain gang."

Wow.

GATES: What's it like to read that?

KHALIFA: Um, it sounds about right, but the fact that he was willing to write in and complain, it seems like it was pretty, you know, pretty unbearable.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: Um, 'cause I feel like most, most of those cats were just used to it.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: But if it's, you know, to the point of writing a letter and explaining what these people's behavior is like, I feel like it, it must have been pretty bad.

GATES: Had to be horrible.

KHALIFA: Yeah.

GATES: In spite of the racism, Wiz's great-grandfather thrived in the army.

He completed his training, was assigned to a truck regiment, and given a rank reserved for men who demonstrated special technical skills.

But even so, Willie was most likely unprepared for what lay ahead.

In December of 1943, with war raging across the Pacific, his regiment boarded a ship and ended up on the island of New Guinea.

KHALIFA: Wow.

GATES: Did you know that?

KHALIFA: No, I didn't know that at all.

GATES: Did you have any idea anybody in your family had been, had lived in New Guinea?

KHALIFA: No.

GATES: By early 1944, his unit was stationed in New Guinea, which is off the northern coast of Australia.

KHALIFA: Okay.

GATES: So, any idea why your ancestor would be there?

KHALIFA: Nah.

GATES: Let's find out.

KHALIFA: All right, let's find out.

GATES: Please turn the page.

KHALIFA: Let's go.

GATES: These are the allied troops during the fight against the Japanese... KHALIFA: Oh, damn.

GATES: ...in New Guinea.

KHALIFA: Oof, that had to be rough.

GATES: And your ancestor was there, can you imagine?

KHALIFA: Yo, that was probably so rough.

GATES: Oh, it was terrible.

KHALIFA: They got big ass spiders out there.

(laughs).

GATES: Yeah, and big ass bullets.

(laughter).

Due to its strategic location, New Guinea was a battleground for much of the war.

The site of ferocious fighting between Japan and the Western allies fighting that claimed over 200,000 lives.

While Willie didn't see combat, there was bloodshed all around him.

Indeed his regimen was likely providing support for soldiers on the front lines.

(whistles).

KHALIFA: Jeez.

GATES: Mm.

KHALIFA: Damn Papa Bush.

Bringing them loads in.

GATES: Yeah, and you know, the Quartermasters, a lot of them got killed because they are... KHALIFA: Yeah, 'cause they're transporters.

GATES: That's right, it was dangerous work.

KHALIFA: Hell yeah, you're in ridin', you're driving into the middle of it.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: Like through it, yeah, yeah.

GATES: And think about this, you had to fight racism... KHALIFA: Yeah.

GATES: ...in your ranks, and then go out, risk your life at the threat of being killed by the Japanese.

KHALIFA: Yeah, and like the, be better you are at getting goods to people, the more that they're going to use you to do it.

GATES: Yeah.

KHALIFA: That's gonna increase your chances of getting blown up.

GATES: Yep.

KHALIFA: He was pretty good.

GATES: He was good, and he didn't get blown up.

KHALIFA: Yeah, he didn't get smoked.

GATES: Willie was discharged on July 3rd, 1944, about one year and eight months after he enlisted.

Let's see what he did next.

KHALIFA: Thank God.

GATES: Yep.

KHALIFA: This is a record from Lamar County, Georgia.

Would you please read that transcribed section?

KHALIFA: "I certify that Willie Wimbush and Clara Ogletree were joined in matrimony by me this 27th day of December, 1945.

That's your great-grandparents' marriage record.

What's it like to see that?

KHALIFA: That's wild, yo.

Never thought I would see nothing like that.

GATES: After their wedding, Wiz's great-grandparents settled in Barnesville, Georgia, where Willie found a job as a salesman, and Clara worked as a maid.

World War II was over, and the American economy would soon be booming.

But the young couple still faced daunting challenges.

Now, you would think that because of the heroism of people like your great-grandfather, race relations would improve, right?

KHALIFA: Uh, no.

GATES: Let's see if you're right.

(laughter).

This is dated August 8th, 1946.

Less than a year after your great-grandparents got married, would you please read the transcribed section?

KHALIFA: "Among the casualties of war 1946, January 4th, four Negro veterans killed in Birmingham, Alabama.

February 5th, two Negro veterans killed in Freeport, Long Island.

February 13th, Negro veterans' eyes gouged out by Aiken, South Carolina, Policeman."

Damn.

GATES: Yeah.

KHALIFA: "February 25th, two Negroes, one a veteran, killed in Columbia, Tennessee jail.

July 17th, Maceo Snipes, veteran.

Only Negro to vote in his district, murdered in Taylor County, Georgia.

July 22nd, Leon McTatie whipped to death near Lexington."

Dang.

"July 24th, four Negroes, two men and two women, lynched by mob in Walton County, Georgia."

Damn.

GATES: During, after World War II, there was an explosion of violence against African Americans in many states, including Georgia.

And much of it was directed toward Black soldiers and veterans who'd returned from the war.

And you could guess why, they had borne arms, they had risked their lives, and they came back and said, "I'm not gonna take this anymore."

KHALIFA: Mm-hmm.

GATES: You know, "This Jim Crow's got to go."

KHALIFA: Mm-hmm.

GATES: And so, they were perceived as a threat, and the racists wanted to take some of them and make them example.

KHALIFA: Mm-hmm.

GATES: You know?

KHALIFA: Yep.

GATES: To try to make them docile again.

KHALIFA: Right.

GATES: Can you imagine serving your country and coming back home to that kind of reception?

KHALIFA: No.

It's crazy that people were expected to just think that that was normal and not fight back.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: Yeah.

GATES: How do you think Willie and Clara felt seeing this in the news?

KHALIFA: Right.

GATES: Hearing about soldiers... KHALIFA: Right.

GATES: ...getting murdered or mutilated?

KHALIFA: I think it was probably really scary just to know that it was happening and it was a possibility, but also to be that young and to not feel protected.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: Yeah.

GATES: Willie and Clara now confronted a choice.

All around them, African Americans were on the move, heading out of the south for the cities of the north and west, part of what we now call "The Great Migration."

Moving meant opportunity.

But it also meant leaving friends, families, and decades of tradition behind.

A dilemma that Wiz understands all too well.

KHALIFA: I feel like in the South there was a sense of familiarity... GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: ...because that's where they come from, but it was also difficult to deal with.

But I think the familiarity, uh, you know, kind of outweighed it because it was like, what are the chances that we could take somewhere else... GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: ...other than being here?

This is kind of all we know.

This is how we grew up.

So, of course, you know, you want better treatment, but I think it might, you know, be difficult because it's like, what does that look like on the other side?

GATES: Takes a lot of courage to move.

KHALIFA: Right, exactly.

GATES: Well, let's see what they did, please turn the page.

Wiz, City Directory, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania... KHALIFA: Alright.

GATES: 1955.

KHALIFA: "Wimbush, Willie; Machine Operator.

Clara, Laboratory Aide, Magee Hospital."

Cool.

GATES: Yeah.

KHALIFA: That's pretty dope.

GATES: By 1955, Willie and his family had had it up and moved north to Pittsburgh.

KHALIFA: Nice.

GATES: And settled down in the Hill District, which, you know, is the predominantly Black neighborhood in Pittsburgh.

KHALIFA: Mm-hmm.

GATES: What's it like to learn this, these details?

KHALIFA: It's really good to learn it, um, just to know, just to feel Papa Bush's ambition through his story.

GATES: Yeah.

KHALIFA: That's what I could feel.

GATES: Yeah.

KHALIFA: Yeah.

GATES: And his courage.

KHALIFA: Courage, yeah.

GATES: Their courage.

KHALIFA: Yeah, yeah.

GATES: Their willingness to roll the dice.

KHALIFA: Yep.

GATES: Because a lot of people left the South in The Great Migration... KHALIFA: Mm-hmm.

GATES: ...but a lot more stayed home.

KHALIFA: Right.

GATES: So that... even in the same family, some people say, "I'm gonna Pittsburgh," and somebody was like, "Where the hell is that?"

KHALIFA: Exactly.

GATES: Go up there, you don't know nobody.

KHALIFA: Mm-hmm.

GATES: Why don't you stay here?

KHALIFA: Right.

GATES: Where the peaches are good.

KHALIFA: It's pretty cool.

GATES: That is pretty cool.

KHALIFA: Yeah.

GATES: Turning to Sanaa Lathan, we found ourselves back in the Jim Crow era, exploring a family with a very different migration story.

It begins with Sanaa's maternal grandfather, Wesley B. McCoy.

Wesley was born in Indiana in 1915, and Sanaa grew up knowing that she had roots in the Midwest, but she knew little more about this part of her family because her grandfather was a complicated man.

LATHAN: I was never really close to him.

He wasn't really around when I was, um, growing up.

But as I got older, I remember he used to come to my plays a lot when I was in drama school, and he would always bring a different woman.

GATES: Oh!

LATHAN: He was a, a real, uh, Casanova till the end.

He would have like three girlfriends and would talk about him.

You know, like, "I like this one because of this..." So, he was definitely a, a ladies' man.

GATES: Do you know anything about his roots?

LATHAN: No.

GATES: No?

Good, it makes you an ideal guest.

LATHAN: Okay.

GATES: It's too bad that Sanaa's grandfather was so focused on his romantic life because his roots were fascinating.

His father, a man named Wesley Deer McCoy, was born in Texas in 1879.

By 1908, he had enrolled at a veterinary college in Michigan alongside another African American named Felix Booker.

At the time, there were only a handful of Black veterinarians in the entire United States.

And perhaps unsurprisingly, Wesley and Felix were not treated well.

After completing their first year, they were denied admission for the following year, solely because of their race.

Many people would've walked away, out of sheer hopelessness, but not these two.

Wesley and Felix sued the school, one of the first anti-segregation cases ever filed on behalf of college students in America.

And your great-grandfather was a part of it; he made legal history.

LATHAN: That's so crazy.

I'm so, I'm surprised that Granddaddy, we used to call him Granddaddy, that he didn't tell us that.

Or maybe I just didn't pay attention, you know?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LATHAN: But I, I, I don't remember this, this is a amazing.

GATES: Isn't that incredible?

LATHAN: Yes.

GATES: I mean, you have a race pioneer.

LATHAN: Yeah.

GATES: Civil Rights pioneer on your family tree.

LATHAN: Yes, I'm so proud of him.

GATES: Yeah, me too.

(laughter).

In court, lawyers argued that a Michigan law dating back to the 1860s prohibited segregation in the state's public schools, and Wesley and Felix won their case.

But when the two men returned to their classrooms, they found that many of their fellow students did not care about the verdict.

LATHAN: "Hanging in effigy a figure representing a Negro student, 34 of the 39 members of the junior class at the Grand Rapids Veterinarian College this morning showed the feeling towards the Negro."

Oh my God.

See, this is where I'm gonna cry.

"Felix D. Booker and Wesley D. McCoy applied and were admitted.

The junior class at once walked out and passed resolutions that they would not attend classes in company with the Negro students.

Later, the students made up an effigy representing the Negro man and hung it in one of the halls.

The class went ahead, but there were only six pupils present.

Four White and two Negroes."

Ugh, God.

GATES: Even though your great-grandfather had won his case in court, he still had to face the racism of his fellow classmates.

LATHAN: Yeah, it's just so sad.

GATES: Imagine sitting through that class.

LATHAN: Yeah.

GATES: Yeah.

LATHAN: You gotta be pretty strong.

GATES: Wesley's strength would soon face another challenge.

Following the lead of its students, the administration of his college decided to appeal the court ruling that had brought him back to class.

Wesley's victory was short-lived.

LATHAN: Yes.

GATES: Grand Rapids Medical College took the case all the way up to Michigan State Supreme Court, which ruled against your great-grandfather.

LATHAN: Mm.

GATES: Both Wesley and his classmate Felix, were forced to leave school without finishing the program.

LATHAN: Mm.

GATES: How do you think your great-grandfather responded?

Imagine how he felt.

LATHAN: I don't know, I don't know.

I mean, I know it didn't feel good.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LATHAN: But it seems like he's a fighter, so I'm sure that that, you know... GATES: Mm-hmm.

LATHAN: ...he continued fighting in some kind of way.

I don't know if it was at school.

GATES: Well, let's see.

LATHAN: Okay.

GATES: Please turn the page.

LATHAN: Oh, I'm so excited.

GATES: This is a record from the year 1913, three years after the article we just saw.

Would you please read that transcribed section?

LATHAN: "Wesley Deer McCoy, 'Mac' comes to us from the state of Michigan, having early learned to love the cow, horse, and dog, decided to make a special study of them.

So, in the fall of 1910, we met him applying for entrance at the Ontario Veterinary College."

Yes!

So is that, that's in... GATES: Canada.

LATHAN: Canada.

He was like, this, "Y'all ain't stopping me."

GATES: That's right.

LATHAN: I love it.

GATES: In 1910, about a year after he was barred from study in Michigan, Wesley left the United States heading north and enrolled in another veterinary college at the University of Toronto.

LATHAN: I said he was a fighter.

GATES: Yep, you were right.

LATHAN: I mean, that was part of his character, I mean, he had to really be, I mean, what a determined, you know... GATES: Yeah.

LATHAN: ...kind of mind and soul to have endured that cruelty... GATES: Mm-hmm.

LATHAN: In that first col... but even just to apply.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LATHAN: You know?

GATES: Yeah, and he had to undertake a search for a vet... veterinary college somewhere.

LATHAN: Yes.

GATES: That would take Negroes.

LATHAN: Yes.

GATES: So, "Dear sir, do you take a Negro?"

(laughter).

After Wesley graduated, he may well have been tempted to remain in Canada, but his family and his heart lay in America, and it seems they drew him back.

That decision would pay off in a big way.

Returning to Michigan, Wesley launched a successful veterinary practice and married Sanaa's great-grandmother.

What do you make of him knowing everything that he went through, the challenges he faced?

LATHAN: I love him.

GATES: Yeah.

LATHAN: I love that, I wish I could sit and have dinner with him.

GATES: Does it change the way you see yourself?

Does it help you understand... LATHAN: Mmm, yes.

GATES: ...how you evolved?

LATHAN: It does.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LATHAN: Yes, it does.

I didn't know this was gonna be such a spiritual journey you're taking me on.

Uh, yeah, and I know I'm gonna go home and really think... GATES: Mm-hmm.

LATHAN: ...about this.

And it's beautiful to think about a life, you know, a full life, and how that kind of has influenced you in ways that you never knew.

GATES: Isn't that fascinating?

LATHAN: It is so, it's so cool, it's so amazing.

GATES: We'd already seen how Wiz Khalifa's family escaped the Jim Crow South.

Now, Wiz wanted to know how they'd survived an even greater ordeal, slavery.

This posed a challenge to our researchers.

Enslaved people we're almost never listed by name in federal documents to learn about their lives, we generally have no choice but to try to find them in the records of the people who own them.

So, we began searching for the White people who may have owned Wiz's ancestors.

It was a painstaking process.

But in the 1870 census for Alabama, we found what looked like a clue.

This is the first federal census recorded after the Civil War.

It lists Wiz's fifth great-grandfather, a man named Howard Williamson, living next door to a White family headed by a man who shared his surname, Thomas J. Williamson.

So, you know what that means, Wiz, we suspected that this White Williamson family had owned your ancestors in bondage during slavery.

KHALIFA: Damn.

GATES: We don't know for sure; it's just coincidence.

KHALIFA: Mm-hmm.

GATES: But they're living next door to each other.

KHALIFA: Yeah.

GATES: And they have the same name.

KHALIFA: Right.

GATES: It looks like a duck, it quacks like a duck, it's probably a duck, right?

KHALIFA: Right, mm-hmm.

GATES: So how does it make you feel to, uh, at this point, reasonably surmise that you just met the White man who owned your family in slavery?

KHALIFA: I think I'm programmed to feel a little bit pissed... GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: But just him owning my family just sounds crazy, that just sounds wild.

GATES: Yeah.

KHALIFA: Yeah, it gives, it gives me a little feel, some type of way about that.

GATES: Can you imagine owning another human being?

KHALIFA: Yeah, it's crazy.

GATES: It's crazy.

KHALIFA: Yeah.

GATES: The whole concept's crazy.

KHALIFA: It's wild.

GATES: Now that we'd identified the man who likely owned Wiz's ancestor, we focused on the records that he left behind.

In the 1850 census, we found a slave schedule for Thomas J. Williamson.

It lists his human property, not by name, but by color, gender, and age.

And given what we knew, a single entry stood out.

KHALIFA: "One Black male, age 14."

GATES: Bingo.

KHALIFA: Yep.

GATES: We believe that that 14-year-old boy is your fifth great-grandfather, Howard Williamson.

KHALIFA: That's crazy.

GATES: What's it like to see that?

(clears throat).

KHALIFA: It is crazy to see him as a nameless person on a grid.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: It's crazy to see him along with four other people, or three other people like property.

GATES: Yeah.

KHALIFA: And to know how valuable that property is, because it's a life, and it's not actually property, it's a person.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: But no name, just a color and an age.

GATES: Yeah.

KHALIFA: Yeah, and, and what sex you are.

GATES: Yeah.

KHALIFA: Yeah, that's pretty, like, that's like a reality check of like how, you know, the world was at that time.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: And even it didn't stop him from, you know, having a family and producing a line.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: But at that time, they wouldn't have thought of him as anything that could have done anything good.

GATES: No.

KHALIFA: Yeah, yeah, it's kind of crazy.

GATES: Wiz's ancestor would eventually decide that he no longer wanted to live next door to the man who had owned him.

In the 1870s, Howard moved his family roughly 30 miles away from Thomas to become a tenant farmer.

But his new life was by no means an easy one.

KHALIFA: "Each farmer who rents a piece of land from some more affluent person has a hard row to hoe.

His land will probably produce half a quarter of a bale to the acre..." Damn.

GATES: Mm.

KHALIFA: "Generally, half of this cotton must go to the landlord, another generous amount must go for provisions, and at least very little for the care of his stock, for the clothing and the proper care of his family."

Damn.

GATES: What's it like to see that?

KHALIFA: It seemed like a lot of hard work for nothing to come from it.

And they just using the land, saying, "Oh, we're, we'll rent it to you," but it's still you working on their land and bringing them what they need, so it's this exact same thing.

GATES: "Wiz, I'm gonna let you work this land..." KHALIFA: Yeah.

GATES: "...and you're gonna make everything that's profit..." KHALIFA: Yeah.

GATES: "...but we gonna subtract a few things before we ascertain the profit."

KHALIFA: Yeah.

GATES: You know?

KHALIFA: Yeah.

GATES: Like "Half of it goes to me right off the top."

KHALIFA: Mm-hmm.

GATES: "Then you ate a lot of pork chops over the last year..." KHALIFA: Mm-hmm.

GATES: You know, all of that kind of stuff.

KHALIFA: Yep.

GATES: So, these guys were always in the hole.

KHALIFA: Yeah.

GATES: Always in the hole.

It was a horrible system.

KHALIFA: Yeah.

He's still a slave.

GATES: Essentially, Wiz is correct, the system virtually guaranteed that his ancestor could never gain economic independence, no matter how hard he worked.

Of course, Howard did have an option to try and change the system.

In the wake of the Civil War, Black American men had gained the right to vote.

The only problem exercising that right could be extremely dangerous.

KHALIFA: "In the southern states, the Negro, if allowed to vote at all, must either vote the democratic ticket or have his vote counted out by a partisan judge of election."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: "If he's too prominent in electioneering or working for the Republican ticket, he shot..." Whoa!

GATES: Hmm.

KHALIFA: "White supremacy means everything those words can possibly imply in the South.

The South is solid and will remain so.

White supremacy is assured.

Speakers who do not believe in the existence of the Confederacy State Rights, Jefferson Davis, and divinity of slavery will not be tolerated.

The Negro must vote right or not at all."

Ooh.

GATES: That is the environment in which your fifth great-grandfather had to decide whether or not he was gonna vote.

KHALIFA: That's crazy.

GATES: In the years following the Civil War, the South was riven by violence against African Americans who tried to vote, enabled impart by the rise of white paramilitary groups like the Ku Klux Klan.

Wiz's ancestor, Howard, likely thought seriously about staying away from the polls or leaving Alabama altogether.

But in the end, he chose a different path.

KHALIFA: "We, the undersigned, registered electors, do solemnly swear or affirm that I will support and maintain The Constitution and laws of the United States and The Constitution and laws of the state of Alabama, and that I am a qualified elector under The Constitution and laws of this state.

Names of electors: Howard Williamson, colored."

GATES: Your ancestor registered to vote... KHALIFA: Oh, cool.

GATES: ...in 1880, in spite of all the racist threats against his life.

KHALIFA: Sweet.

GATES: How do you think Howard felt about voting?

KHALIFA: Whatever he was, uh, believing in at the time, he was willing to put it all on the line for it.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: Yep.

GATES: He said, "I'm, I'm not a slave anymore."

KHALIFA: Absolutely, 100%.

GATES: Voting was not Howard's only legacy; he left behind at least seven children and 20 grandchildren.

And seeing this part of his tree laid out, connecting Wiz to his enslaved ancestors would prove deeply moving.

KHALIFA: Yeah, I love that.

GATES: What do you think they would've made of you, a Hip Hop singing descendant?

KHALIFA: I think they would be freaking proud.

(laughs).

They'd be proud that I own some stuff for myself.

They'd be proud of the attitude that I carry, the confidence that I have.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

KHALIFA: The love that I have for my family, the appreciation that I have for what they've done, and even I feel all of them around me, I just don't know who they are, so now I'm able to say their names, so that just makes it even, even better.

(laughter).

GATES: That's beautiful, you can say their name.

KHALIFA: Yeah.

GATES: Their names will never be lost again, so they're not dead, they, they haven't disappeared.

KHALIFA: Yep, absolutely.

GATES: We'd already traced Sanaa Lathan's maternal roots, introducing her to an ancestor who'd moved to Canada and reshaped his family's fortunes.

Now turning to Sanaa's father's ancestry, we were about to meet a man who'd reshaped his entire family tree.

The story begins with a 1950 census for Philadelphia, where we found Sanaa's father as a 4-year-old boy living with his single mother and older brother, a time of his life that he rarely discussed.

What's it like to think of your father as a 4-year-old?

LATHAN: I, I've got emotional just now.

Um, it's, it's surreal, 'cause he's always been such a, you know, a serious, you know, he's the head of the family, he's a, a director, he's, he's in charge, and so to think of him as like a little... GATES: A vulnerable little boy.

LATHAN: Yeah.

GATES: Yeah.

LATHAN: It's emotional.

GATES: When this census was recorded, Sanaa's father was being raised by his mother because his father, a man named Stanley Edward Lathan, had left the family, and no one knew where he'd gone.

We found Stanley in the 1950 census for Boston, working in the kitchen of a restaurant and living in what was known as the Rufus Das Hotel for Men.

LATHAN: Wow, that's wild, I mean, it looks like they were workers.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LATHAN: That looks like a place where you come to work.

GATES: Well, you're right.

The hotel your grandfather was staying in was something between a boarding house and a homeless shelter.

LATHAN: Mm.

GATES: It provided dormitory facilities at a nominal fee every time he wanted to stay there, he would register for bed in the evening, then check out in the morning, every day.

LATHAN: Wow.

GATES: Likely to go to work at the restaurant, or he was working in the kitchen, and then repeat the process all over again to keep a roof over his head.

Did you have any idea... LATHAN: Nothing.

I know nothing.

GATES: ...of what had happened to your father's father?

LATHAN: No, I mean, I knew he did struggle with alcoholism, and that was, that's all that my grandmother told me.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LATHAN: But other than that, I didn't know anything.

GATES: We now tried to trace Stanley's roots and encountered a mystery even bigger than his life.

Records show his father was a man named William Edward Lathan, and that he was born in North Carolina in 1880 to a woman named Caroline Lathan.

But that's where the paper trail ends.

Despite our best efforts, we could not name William's father.

There was only one hope left, DNA.

So, we reached out to Sanaa's father and focused on his Y DNA, the type of DNA that has passed, virtually intact, from father to son, across generations, and it led us to a startling discovery.

Sanaa's father's line leads directly to a White man with a surname Sanaa had never heard before.

LATHAN: "Male of likely European ancestry with the surname of Slade."

Slade.

GATES: Slade, S-L-A-D-E.

LATHAN: Mm-hmm.

GATES: According to your father's DNA, your father's biological surname and thus yours, is Slade.

It is not Lathan.

LATHAN: I like Lathan better.

(laughter).

I like the name, I like the, that way it rolls off the tongue.

GATES: Sanaa Slade.

LATHAN: Sanaa Slade?

GATES: Starring Sanaa Slade.

LATHAN: No, I don't, I don't know.

It sounds like a stage name, Sanaa Slade.

Maybe that'll be my new alias, when I, you know... GATES: Yeah.

LATHAN: Stay in a hotel.

GATES: There you go.

We now knew that William's father was a Slade; we also knew that he was a White man who had fathered a child with a Black woman sometime around 1880, but his full name still eluded us.

So, we turned back to Sanaa's father's DNA and started looking for matches in publicly available databases, hoping to find clues that would lead us to the final piece of the puzzle.

And in the end, we got lucky.

Turn the page.

LATHAN: This is so exciting.

GATES: Would you please read the names of your great-great-grandparents?

LATHAN: Thomas Bog Slade.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LATHAN: I don't know why that makes me laugh.

Thomas Bog Slade and Caroline Lathan.

GATES: What's it like to learn that?

LATHAN: It's amazing.

It's, it's mind-blowing firstly, that you can get that information from, you know, a... GATES: Spit.

LATHAN: Some spitting into a tube.

I mean, it's fascinating and, you know, it just sparks the imagination.

GATES: Yeah.

LATHAN: You know?

GATES: Well, let's let your imagination roam a bit.

LATHAN: Yeah.

GATES: White man, it's 1880.

LATHAN: Mm-hmm.

GATES: Civil War's long gone.

LATHAN: Mm-hmm.

GATES: 15 years later.

LATHAN: Mm-hmm.

GATES: A White man and a Black woman.

If it were slavery, you would say, well, the master raped the woman.

LATHAN: Right.

GATES: But it's not in slavery.

LATHAN: I don't know.

He was probably good-looking.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LATHAN: Because, you know, all the Lathans are, are fine.

(laughter).

Um, so maybe, you know, and she probably was too, and they just, you know, I don't know, it was such a complicated time.

GATES: Right.

LATHAN: So, it's hard to romanticize anything knowing those circumstances.

GATES: Yeah.

LATHAN: You know?

GATES: There's no way to know the nature of the relationship between Caroline and Thomas.

All we can do is speculate.

And as we looked into Thomas's life, we found something that made our speculations even more complicated.

LATHAN: "Confederate Thomas B. Slade, private company, K, 41 Regiment, North Carolina troops enlisted October 27th, 1861."

Wow.

GATES: So, there is your great-great-grandfather, he joined the Confederate army roughly six months after Fort Sumter and served for at least three years.

So, what do you make of this guy?

This is your blood ancestor.

You have DNA from this dude.

LATHAN: Mm-hmm.

GATES: He fought to protect the institution of slavery... LATHAN: Mm-hmm.

GATES: ...as a young man.

And then 14 years after the end of the Civil War, he fathered a child with a Black woman.

LATHAN: Mm-hmm.

My brain is gonna be sore tomorrow.

GATES: Your family story embodies the complexities of race... LATHAN: Yes.

GATES: ...in the United States in a way that Hollywood movies never even touch.

LATHAN: Yeah.

GATES: It's in cartoons, you know, it's all black or all white.

LATHAN: Yeah.

And that's, yeah.

And that's where I feel like we, you know, as you know, Black filmmakers in Hollywood... GATES: Mm-hmm.

LATHAN: Need to go and to, you know, bring the nuance of the Black experience.

I mean, this is interesting.

GATES: It is.

I wanna show you something else about your Slade family.

LATHAN: Mm-hmm, I'm scared.

GATES: A very important element, would you please turn the page?

LATHAN: Okay.

GATES: See, before you were turning those pages in advance, now you're terrified.

LATHAN: I know, now I'm like "I don't want to turn..." okay.

GATES: We're back to 1860.

This is a year before the Civil War breaks out.

LATHAN: Mm.

GATES: And it's the 1860 census for Williamston, North Carolina, just one year before Thomas enlisted to join the Confederate army.

LATHAN: Mm-hmm.

GATES: Would you please read what we've transcribed for you in that white box?

LATHAN: "Penelope Slade, age 48, widow.

Thomas Slade, age 15.

Helen, age 13.

Fanny, age 11.

Richard, age nine."

GATES: There's Thomas, your ancestor, when he was 15 years old.

LATHAN: Mm.

GATES: Living with his siblings and his mother.

LATHAN: Mm-hmm.

GATES: That lady is your third great-grandmother.

LATHAN: Penelope, wow.

GATES: That White lady is your third great-grandmother.

LATHAN: Mm.

GATES: You know, at first when you're introduced, you think, "Well, I have one White ancestors," you got all these White ancestors.

All of his ancestors are your ancestors.

LATHAN: Right?

I guess so, huh?

GATES: We now set out to see what we could learn about Penelope.

Records show that she was likely born in North Carolina sometime around 1810.

And by the time the Civil War broke out, she was a widow raising seven children, including Sanaa's great-great-grandfather Thomas.

Digging deeper, we saw that Penelope was also a slave owner.

According to the 1860 census, she owned 43 human beings.

(groans).

LATHAN: I guess it's not all sunshine and roses, right?

GATES: No, and guess... LATHAN: That's the, that's the eternal optimist in me.

GATES: And guess what, that was a lot of slaves.

LATHAN: That is a lot.

GATES: In 1860, only 1% of White families in the United States own 40 slaves or more.

Only 1%.

You know, we talk about the 1%.

Your family was in the one... LATHAN: So, she, she was in the 1% of slave masters.

GATES: Yes.

What's it like to see this in black and white?

LATHAN: I mean, I, I, I, there's, you know, I'm so, so layered.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LATHAN: With so many, like any human being, and so it's, it's just fascinating to think of all these different people that have kind of contributed to the soup that I am.

GATES: Yeah.

LATHAN: You know, it's like, you know, my mother kind of taught me to pray to, you know, my angels, who are many of our ancestors.

GATES: Yeah.

LATHAN: And so now, you know, I have more of an idea maybe.

GATES: Yeah.

LATHAN: When I, when I do pray.

GATES: Well, do me a favor, when you pray to those confederates... LATHAN: I don't know about Penelope, though.

GATES: ...send me an email... LATHAN: I don't know if I'm gonna be, you know, praying to... GATES: "Dear third great-grandma Penelope.

I am your new third great-granddaughter."

LATHAN: Exactly.

GATES: How you like me now?

LATHAN: How you like me now?

Exactly.

GATES: The paper trail had now run out for each of my guests, it was time to show them their full family trees.

LATHAN: Wow.

KHALIFA: Sheesh.

GATES: And see what DNA could tell us about their deeper roots.

For Wiz Khalifa, this would yield a surprise as we tried to match his genetic profile with that of other guests who'd been in our series, searching for distant cousins, Wiz never knew he had.

And often there's no match.

KHALIFA: Mm-hmm.

GATES: But in your case, there is.

KHALIFA: Ha!

GATES: You have a cousin that you never, ever could've imagined.

KHALIFA: Yes.

GATES: You ready to meet your DNA cousin?

KHALIFA: Yes.

GATES: Turn the page.

KHALIFA: Oh-ho, yes.

Oh, for real.

GATES: Ava DuVernay.

KHALIFA: Christ.

GATES: Ava DuVernay is your DNA cousin.

KHALIFA: What up, cuz?

GATES: Wiz's mother shares a long, identical segment of her X chromosome with the Emmy Award-winning director, Ava DuVernay, meaning that the two have a common ancestor somewhere in the branches of their family trees.

KHALIFA: Well, everybody, now y'all know me and Ava are cousins.

GATES: Yeah, isn't that amazing?

KHALIFA: Yeah.

GATES: She's a brilliant filmmaker.

KHALIFA: She's really, really good.

That's awesome, bro.

GATES: Sanaa Lathan was in for a surprise of her own.

(gasps).

LATHAN: Oh my goodness.

(laughs).

GATES: We discovered that Sanaa shares a long, identical segment of her 14th chromosome with the renowned actor Sterling K. Brown.

LATHAN: I love it.

GATES: Have you two ever worked together?

LATHAN: No, but we actually did some charity work together.

GATES: Oh.

LATHAN: And I know him and his wife, and they're wonderful people, and obviously, he's so gifted as an actor.

GATES: Well, when you have your family reunion, you have an additional person.

LATHAN: I have to invite him?

I love it.

GATES: That's the end of our journey with Sanaa Lathan and Wiz Khalifa.

Join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of Finding Your Roots.

Sanaa Learns About Her Paternal Grandfather’s Journey

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S12 Ep2 | 4m 7s | Sanaa learns about her paternal grandfather's roots and struggles. (4m 7s)

Wiz Khalifa Discovers His Ancestor’s Courage to Vote

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S12 Ep2 | 4m 8s | Wiz learns about his ancestor's courageous decision to register to vote. (4m 8s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: